Interview by Milan Vukmirovic

Mitchell Feinberg began doing still-life photography as a teenage hobby. At 21, he left his native New York for Paris to learn more and pursue a career as a professional photographer — a move that came with thrilling highs and unexpected lows. Forty years on, Feinberg is one of the world’s top contemporary still-life photographers; his clients include Estee Lauder, Tom Ford beauty, Cartier, Bulgari and Fenty, among many others. I consider myself lucky that we met many years ago and have been able to collaborate first on L’Officiel Hommes and now on Fashion For Men. I’m also proud to call Mitch my friend. But beyond that I believe he’s a genius, a living legend with that rarest of all attributes: discretion. So it felt only natural to showcase his story in this new digital-only iteration of FFM. And he was kind enough to share a few treasures, which we proudly feature with

this interview.

MV: Hi Mitch! It’s been a long time — I was launching L’Officiel hommes and we were both still living in Paris. But actually, you grew up in the US.

MF: Yes, I was born in the Bronx, in New York, and spend my first years in Yonkers, just north of there. Then my parents moved to Westchester, as so many families did in the Sixties. So I spent most of my school years in the suburbs, which I really hated. I thought it was really boring, I didn’t like my school, a public school. I felt like a total outsider. Early on, as a teenager, the only thing I loved doing was taking photographs. I installed a darkroom in a bathroom of our house so I could develop my own film rolls.

MV: What were you photographing back then ?

MF: Mostly plants and, already, some still-lifes. Many years later, when my parents decided to move again, my parents asked me to come and take all those pictures from that time or else they’d have to throw them out.

MV: Were you doing indoor or outdoor photography?

MF: Both. But when it was inside I was using our little house lamps (laughs).

MV: So already you liked working alone. Still-life photography is a pretty solitary passion.

MF: Yes, true. I never really needed a lot of social interaction to feel fulfilled. Photography was my true passion.

MV: What was your first love about? Creating beautiful images? Making art?

MF: I have no idea. But 45 years later, looking back at these prints of my early work that my parents made me take back, I realize that even though my technique has improved and evolved, I am still kind of doing the same thing (laughs). Of course, what I shoot now is much more interesting and creative, but I can see that there is still a direct link between what I was doing then and what I am shooting now, at 60 years old.

MV: In fashion, it’s very rare to see a photographer who shoots models also doing still-life. I understand now that the technique, the timing is different. Mostly, it’s that still-life demands patience and meticulousness.

MF: But mainly — and mostly — a lot of self motivation.

MV: When were you able to really make a living from your chosen profession?

MF: Well, my career started in a very particular way. I went to university but after a year I really wanted to change my life, and already at 21 I wanted to get away from my family.

MV: For Europe. So, New York in the early Eighties wasn’t exciting to you?

MF: It was. And by leaving, it wasn’t because I didn’t love my parents. I just felt a need to be independent but also to try to learn another way of life. At that time, Europe was an exciting place for a photographer to have another point of view, another way of life. So I choose Paris, which at that time was exciting for fashion, style and creativity.

MV: You arrived in Paris in 1984, the golden age of Le Palace and creatives in Paris.

MF: Definitely. I actually went to Le Palace club a lot at the time (laughs ). Les Bains Douches, too. It was an amazing time and the best way to meet so many cool and creative people. And for me, as an American in Paris, having dollard was a great way to live the good life without of lot of money. I had lots of fun and wasn’t very ambitious at first. My intent was to first get a job as an assistant. So I got like three photographers’ phone numbers and contacts at the time and the first job interview I got was with Jean Louis Bloch Lainé, who looked at my work and told me right away that he thought I was wrong to look for a job as an assistant. He thought I should just go for it and become a photographer right away. Also, that assisting would probably kill me.

So I followed his advice and it took me a year to put a proper book together and try to get a meeting with the person he thought was the only one to meet at the time: Peter Knapp.

It definitely wasn’t easy, but after many calls, I met Peter. After looking at my work, he gave me my first pages in Femme magazine, which was then owned by Hachette and wanted to compete with French Vogue. They had a big budget and they wanted to compete in the same luxury market. Funnily enough, when Femme launched and the Vogue people saw my pictures, they called me right away. It was great for me but I didn’t want to be seen as an opportunist or a traitor to Peter. So I told him about the Vogue opportunity and that I wouldn’t let him down. But he said, no — if they want you, you should go. So at 23 years old I officially started to work for Vogue Paris alongside others like Helmut Newton etc… it was like a flash of lightning in my early career, when I didn’t even really know which were the right labs to work with, who could develop my film, I didn’t have anyone to negotiate contracts for me. I made a lot of stupid mistakes. But quickly I had advertising jobs like for Gucci fragrances and I had never made so much money. I was living like a young king but a very stupid one (laughs) and it became a real problem. After two or three years I’d lost touch with reality and I made bad choices, burned through the money I had, and slowly lost jobs… It took me years to recover. I had the tax people chasing me, I was arrogant and my ego just made it all worse.

MV: But how did you lose all that money? Were you partying all the time? Not saving a dime?

MF: It was a crazy time but my biggest mistake is that I didn’t have someone to take care of the business side of my work, the deals, contracts etc. Someone who could guide me and keep me grounded. So after almost lost everything, I started over from the bottom and did pack shots

MV: How long did that difficult period last?

MF: Three or four years. It was really hard. It was the late Eighties, early Nineties.

MV: What were people saying about you at the time?

MF: ”He’s very difficult, he doesn’t listen, etc. La grosse tête, as the French say.

MV: So how did you get back on your feet ?

MF: I had no other choice than to do very commercial money jobs that could pay the bills. Like pack shots. But somehow I guess it all happened for a reason and, during that time, while I was doing very commercial jobs for Cartier, for example, which was one of my main clients, I learned a lot about the technical side of my work, and how important and precise lighting is, for example.

MV: Do you agree that sometimes you just have to hit rock bottom in order to succeed again?

MF: I think there are ups and downs in every photographer’s career. Even Mr. Penn had waves. I just had to survive and get out of debt.

MV: Irving Penn was the master of 20th century still-life photography. Was he a big inspiration for you? Did you ever meet him?

MF: He was my biggest inspiration. I always wanted to meet him but never got the chance. I have worked with people who worked with him. I tried asking a few people in his orbit to help me meet him, and they always told me that although he was a nice man, he didn’t really like to meet people. Funnily enough, later I was asked to shoot for American Vogue a few times when he didn’t want to shoot or wasn’t available… I did try to get that introduction, but it never happened and I understand and respect that he couldn’t.

MV: We met almost 20 years ago when I asked you if you would shoot for me and L’Officiel Hommes Paris. Over the years, we did some amazing stories. Some pictures you did for me are still so iconic and beautiful. You regularly work for Elle US and the WSJ. You count Cartier, Tom Ford beauty, Bulgari, and Estee Lauder among your clients. After all these years, you’ve became one of the best if not the best still life photographer working today. But what always strikes me is how discreet you are. Why is that?

MF: I’ve always been very discreet and I’d rather people know my work than recognize me (laughs)

MV: I can’t even imagine how many images you have created. Haven’t you ever considered publishing a monograph of your best work, or doing an exhibition?

MF: I have been approached by some people but to be honest what I do really like and enjoy is taking pictures. I don’t feel the need to do an exhibition yet. I am still motivated by photography. Maybe I’ll do a book someday, but that day hasn’t come yet. If someone asks, I say no. I don’t know why. But no, I’m not ready.

MV: When we met you were still shooting entirely on film. At some point you made the transition to digital. Was that difficult for you?

MF: Yes, very. I do miss shooting on film, a lot!

MV: Because of film’s quality?

MF: Yes, the quality but also the process. It took more time to shoot on film, but I used to like having that time to take pictures. The rigor of it. And it suits my process. Also, somehow clients were not reading Polaroids well, so they had to trust me and the process more until the result came out on film and was delivered to them. Today, the client is behind you during the shoot, looking at the screen while you are taking the pictures and asking me almost in real time to change this or that.

MV: But digital offers amazing quality now as well as post-production possibilities, retouching etc.

MF: Yes, that’s true, now I shoot all my work in digital. And I can shoot faster and do more pictures in one day. Still, for me the real luxury is to try to do as much as possible to get the best picture in a shot. I try to avoid retouching as much as possible. It’s not about trying hard without the help of technology. But for me, I want make a point of trying hard to make the best picture as good or perfect as possible while I shoot. I think that effort is the quality that people will see and feel. Technology should just help as a final touch, or an assist that never should be noticed. That’s how you keep things real. It’s not the technology that motivates me.

MV: You like keeping things as real as possible?

MF: Yes, again that’s my luxury. When people see my pictures, they know they’re real. Every decor or set is real, the bag or whatever I shoot is real, it’s there. I don’t like spending time behind a computer screen creating or recreating a composition.

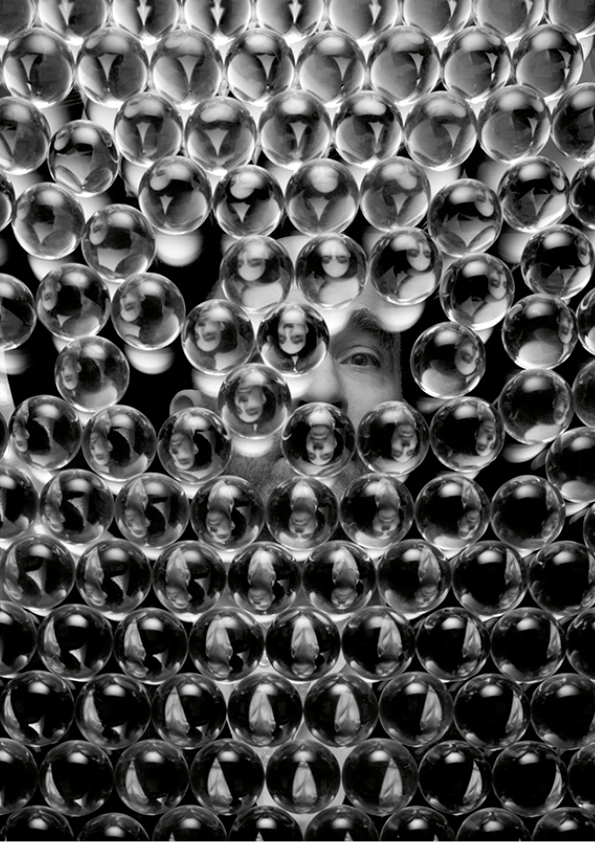

MV: That reminds me of some of your requests when we were shooting. They weren’t always easy. Sometimes you kept it simple and just used lights to make magic; at others you did these very complex sets with tons of props, beads, cut-outs, to name just a few. Are you more excited about the shoot when it’s more complicated or challenging?

MF: Yes, that’s what’s exciting and magical to me, making it all as perfect as possible to get the perfect shot. I don’t cheat through post-production. I like the true reality of an object, a bag, a shoe, a perfume bottle, or whatever, in an amazing yet calculated and prepared artificial set. That’s were I get to express creativity. You just need to know the techniques and the technology that will help you to get the beauty you want to achieve.

MV: You must be so patient: some of your pictures require a crazy amount of work and preparation.

MF: More passion than patience. I can spend hours and hours, sometimes days, to get the perfect picture. It drives me crazy sometimes, but I know it’s worth it.

MV: It’s a bit sado-masochistic, no? To embrace what’s tough in the pursuit of ultimate pleasure or satisfaction?( laughs)

MF: ( Laughs) I don’t know about that… But I am always motivated to try do something that hasn’t been seen before.

MV: You love the challenge.

MF: Yes, definitely — even if it takes time, that doesn’t matter. The challenge of doing something I’ve never done before keeps me going.

MV: After decades and thousands of shoots, what do you see as the future of still-life? For you personally and in general?

MF: Artificial Intelligence, for sure. Now you can type “create an image with this Perrier can in the style of Irving Penn” and you will get an image that is pretty amazing even if the can didn’t yet exist in Penn’s lifetime. It’s fascinating.. And it’s only the beginning of this incredible technology.

MV: But AI is inspired by what already exists.

MF: Yes, and yet it’s mixing so much data that what it produces is something you’ve never seen before. And I think soon it will kill still-life photography.

MV: Maybe not just because of AI. There’s also this new generation of creative people who are more keen to work toward video, or animation. Moving images seem like more of a threat to still-life. Music comes with that, and so on. It’s more entertaining, and social media is the perfect platform for it.

MF: Motion is the thing right now in the still life industry. I do a lot of videos now. It’s predominant across the industry. In every important launch today, for a new fragrance, for example, I’m being asked to do still-life pictures as well as moving images, videos with the actual fragrances in the same mood and light set. It takes more time and a bigger crew. There’s a lot of pre-production before the actual shoot. A lot of post-production, editing and special effects, too.

MV: As genius as AI is, I still think that to create images — animated or not — we will still, always, need true creatives like you to fuel AI.

MF: If AI could help me create, that could be exciting and challenging. The genius of Richard Avedon or Irving Penn wasn’t about how, who or what they were shooting, it was about their vision or their soul that we could feel through their photography. In the end, a true creative vision is about an individual and unique creative spirit. I won’t ever change my work or who I am, but if AI can be part of its evolution then why not?

MV: So we’ll leave you with just a wish: we hope to see a book of your best work. When people see these shots, they’ll understand my frustration because I just want to see more. Thank you Mitch for taking the time.

MF: Thank you !